Star Quality

Star Light, Star Bright… the next time you look up to the stars consider the important role these giant balls of gas have played in navigation over time.

“I must go down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and sky

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by…”

In this season of goodwill to all, it is interesting that be it the guiding star for John Masefield’s sailor in his classic poem ‘Sea Fever’ or the biblical ‘star in the east’ that is followed by the three wise men of old, it is a knowledge of the stars that from the earliest days has been an essential point of reference for long distance travellers.

Man’s association with the stars goes right back to our earliest pre-history, as our ancestors looked upwards in wonder before working out that there were patterns in the night sky that varied with the seasons. The likelihood is that these first-generation astronomers would have associated what we now refer to as the constellations with whatever was happening in their lives at that time of the year, with the very term constellation harking back to the Latin constellatio or ‘set of stars’.

There is clear evidence in the form of clay tablets that as far back as 3,000BC the Mesopotamians (nowadays Iraq) had created series of constellations, with these being refined by the Babylonians, but it was the ancient Greeks who named many of the collections of stars with characters from their colourful mythology.

What is even more amazing is these foundations of astronomy were taking place at a time when many thought the world was either flat or worse, flat and balanced on the back of a turtle (or an elephant, depending on where you were). Yet more than 500 years before the “we three Kings of Orient are” learned travellers from Africa had worked out that there was a different set of constellations in the Southern sky and had started to assign names to them.

GROWING KNOWLEDGE

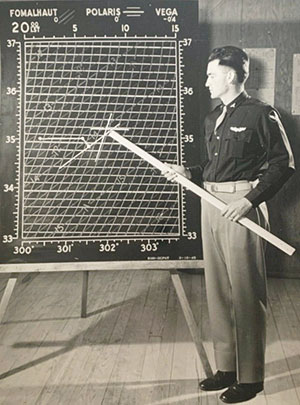

With long night flights over the blank vastness of the Pacific Ocean, astro navigation was a key skill for US aircrews, with the subject being carefully taught. Here is the result of some careful plotting as the navigator’s position should be somewhere inside that small triangle where the three lines intersect. Image: US National Archives

By the 2nd century CE, the Greek astronomer Ptolemy would be producing his ‘Almagest’, an incredibly detailed catalogue that described not only the position of the clearly identifiable stars but their magnitude in brightness terms. This greater awareness of the movement of the stars would then lead on to be used as a way of navigating longer distances, be that on land or out at sea, which helped drive the growing pace of not just exploration but international trade.

By the time the Vikings were heading westwards across the Atlantic to discover the North American continent, the principles of astro navigation were already becoming more clearly understood, though in practice the methods of calculating a position remained fairly crude, which at best could only give an approximate location.

Part of the problem was that whilst there were techniques that aided the measurement of the angle of a celestial object, be that the sun or a star which will give an indication of latitude, longitude would be a much more difficult equation to solve. As long as you had some idea of the speed of the boat, you could calculate how far you had travelled (speed x how long you had been travelling for) but this only really became of value once you knew, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, how far you still had to go before you ran out of water and hit the land.

As long offshore voyages helped develop our understanding of the known world the need for better navigational skills grew ever more demanding. This demand had two key aspects, the first of which was the need for better maps, as whilst the seas around Europe were becoming charted, the world maps of the late Middle Ages could only reflect the world as it was known then.

When, in late 1520, Ferdinand Magellan headed westwards into the Pacific away from the tip of South America he was heading for the Spice Islands, which the maps of the day suggested were just a couple of days sailing away over the horizon. The portion of the world map that covers the vastness of the Pacific simply did not exist at that point and would not do so until the explorers of the Renaissance period were able to add in the missing details.

EVERMORE ACCURATE

It would be another 250 years before John Harrison, an innovator based in Yorkshire, finally developed his H4 chronometer with this allowing the practice of accurate shipboard time. It would only take a few more years before a French team demonstrated the measurement of longitude onboard the ship Aurore.

In theory, the process they followed remains the same today and is fairly simple, with the angle between the horizon and a known star being measured with a sextant. This figure, along with the exact time, is then used in conjunction with a maritime almanac to create a ‘Line of Position’, which is itself just a short segment of what is in effect a large circle on the surface of the globe.

As more sights are taken using other celestial bodies, more positions are plotted and where they intersect has to be the location that the sightings were being taken from. This is very much a simplification of what in practice is a more complex process which also involves reduction tables and other calculations, but it was now possible to get remarkably accurate fixing of both the latitude and longitude positions. Today, with even more accurate timekeeping, an experienced navigator can take a ‘fix’ that will position the user to a point within a nautical mile.

NASA’s Orion capsule will travel further from earth than any previous human rated spacecraft. In order to return safely to earth, Orion’s location has to be calculated in three dimensions, which they do by following the stars, just like the sailors of old. Image: Shutterstock/Dima Zel

KEEP ON SHINING

The sailors may have perfected the technique but they would not be the only masters of steering by the stars, as during WW2, with the continent of Europe ‘blacked out’, the RAF bombers would navigate their way on night-time missions by taking star sights, with the task being eased by the construction of a special clear canopy (an Astrodome) that allowed the navigators an un-interrupted view of the night skies.

However, the war years had also seen the introduction of electronic navigational aids and as these got ever more sophisticated, accurate and cheaper, to the point that today even a dinghy can carry a GPS receiver, the expectation was that astro navigation would go the way of Morse code and lead lines.

But the resilience of star sights, which mean that they cannot be jammed, saw the cold war ballistic missiles steering by the stars and, launched just last month, the Artemis moon mission (testing a rocket and capsule that could return astronauts to the Moon after 50 years) uses an advanced form of star sight navigation to stay on course as far as the moon and beyond.

Our forebearers looked up to the night sky in wonder, then in more recent times we have followed stars, as they took us in the right direction. In the not too distant future, when we finally head to the stars, we will be using them to find our way, just as those early navigators on sailing ships did so many years ago!

Solent based dinghy sailor David Henshall is a well known writer and speaker on topics covering the rich heritage of all aspects of leisure boating.

Solent based dinghy sailor David Henshall is a well known writer and speaker on topics covering the rich heritage of all aspects of leisure boating.

The post Star Quality appeared first on All At Sea.