La bomba que rebota

Este mes hemos estado descubriendo más sobre la fascinante historia detrás de la bomba que podía saltar sobre el agua.

Tal vez sea un triste reflejo de la psique británica que uno de los anuncios de televisión populares de principios de la década de 1990 presentaba a un bebedor de una conocida marca de cerveza rubia que "rebotaba" su toalla en la piscina para aterrizarla en un lugar privilegiado Tumbona española , todo al son del tema Dam Busters.

Unos 20 años antes de la votación del referéndum sobre la salida de Europa, había un indicio innegable y subyacente de xenofobia en nuestro personaje, pero al mismo tiempo, la icónica incursión en tiempos de guerra en las presas alemanas utilizando la 'bomba que rebota' de Barnes Wallis es algo que tenemos. todos los motivos para estar orgullosos.

Hace 80 años, esta primavera, un escuadrón de bombarderos Lancaster modificados despegó del aeródromo de Scampton, volando hacia el sureste sobre territorio enemigo antes de descender en picado por debajo de lo que hoy sería la altura del tope, en la oscuridad total, para hacer rebotar sus bombas en la superficie. del agua y en las enormes presas. No es de extrañar entonces que esta sea una acción que hoy, incluso después de tantos años, todavía despierta los sentidos, ya que la valentía, sin mencionar el sacrificio de tantas vidas, más la ingeniosa innovación detrás del arma, todo habla de ' Gran Bretaña en su mejor momento'.

Sin embargo, lo que puede sorprender a nuestros lectores es cuánto del desarrollo original de la idea (para la cual Barnes Wallis obtuvo con éxito una patente en agosto de 1942) tuvo lugar en algunos de nuestros tramos de costa más populares.

OBTENER LOS HECHOS CORRECTOS

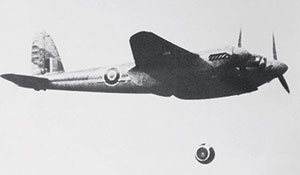

Un Mosquito del Escuadrón 618, la unidad hermana del Escuadrón 617 que rompe represas, lanza una prueba de 'highball', la versión antibuque de la bomba que rebota

Imagen: Ministerio de Defensa

Algunas de estas lagunas en nuestro conocimiento provienen de la película de 1955 The Dam Busters, ya que como fuente de información tenía graves fallas. En el momento en que se hizo la película, la tecnología detrás de la bomba que rebota todavía estaba firmemente en la Lista Secreta, lo que obligó a los productores a realizar una serie de trucos fácticos. Uno de los más grandes forma la primera parte de la película, donde el paternal Barnes Wallis se enfrenta a los poderes de la autoridad para que su idea sea aceptada, y aunque esto resultó en una película emocionante y cautivadora, simplemente no se ve confirmada por la hechos.

Para empezar, la idea de atacar una serie de represas alemanas era anterior al estallido de las hostilidades, ya que ya estaban en una lista de objetivos de alto valor dignos de ataque, cuando tuviéramos la capacidad de hacerlo. La idea tampoco era exclusiva del Reino Unido, ya que los alemanes también tenían en la mira una serie de represas en el Reino Unido, pero también carecían no solo de un arma viable, sino también del avión pesado de largo alcance capaz de entregarlo.

Nada de esto importó, ya que una vez que se abrieron las hostilidades, las presas pronto fueron protegidas por una serie de redes antitorpedo.

LEJOS DE NUEVO

A pesar de que Barnes Wallis tomó la idea, los principios básicos estaban lejos de ser nuevos, ya que en los días nelsonianos se sabía que un disparo disparado en una trayectoria muy poco profunda podía saltar a través de la superficie del agua, aumentando potencialmente el alcance al que el enemigo podía disparar. estar comprometido.

Los registros contemporáneos hablan de oficiales de artillería que desarrollaron una pieza de hierro curvo que, cuando se colocaba en la boca del cañón, daba un giro al disparo, lo que hacía que volara más certero y rebotara más. Se descubrió que hacer girar el tiro era muy importante, ya que esto pone en juego el Efecto Magnus (el Efecto Magnus lleva el nombre de Heinrich Magnus, quien en 1852 investigó el fenómeno de un objeto giratorio que se mueve a través de un fluido, aunque Isaac Newton había descrito el efecto allá por 1672!).

Sin embargo, sería Barnes Wallis quien abordaría el asunto en un ataque sistémico y multifacético. Por un lado, instigó una serie de experimentos con algunos pequeños modelos de presas para ver cómo podrían romperse mejor por una explosión que ocurriera cerca. Al mismo tiempo, jugó un papel decisivo en la exploración de cómo se podía hacer que un arma lanzada desde el aire no solo rebotara, sino que mantuviera el rumbo deseado hacia un objetivo. Aquí la película lo hace bien cuando experimentó en su jardín con canicas lanzadas desde una catapulta a un estanque, antes de que los alentadores resultados lo llevaran a ampliar sus pruebas en el tanque de prueba cerca de Teddington.

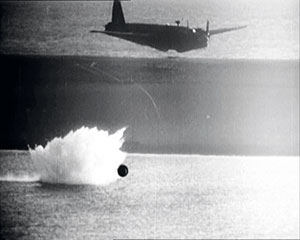

Con Chesil Beach como telón de fondo, un bombardero Wellington completa uno de los primeros lanzamientos de prueba de una bomba que rebota

Imagen: Ministerio de Defensa

Lo que es clave, sin embargo, es que a medida que la bomba que rebota pasó de ser una buena idea en el papel a convertirse en un arma altamente efectiva, durante mucho tiempo la idea de que sería un objetivoEl ataque a las presas era una consideración secundaria, ya que se consideraba la forma ideal de atacar a los buques de guerra de la capital de Alemania, con todos los ojos puestos en el temido Tirpitz.

Los torpedos todavía eran relativamente lentos y aún no estaban guiados, por lo que la perspectiva de un arma antibuque rápida y precisa significaba que fue el Almirantazgo el primero en impulsar la siguiente etapa de desarrollo. Barnes Wallis se dio cuenta rápidamente de esto y cuando el Equipo Superior del Almirantazgo vino a verificar su progreso, ¡se aseguró de que la presa modelo que habían estado buscando fuera reemplazada por un acorazado modelo!

Parte de la atracción para el Almirantazgo provino de la acción giratoria de la bomba, ya que cuando finalmente alcanzó el costado del barco, todavía estaba girando y, por lo tanto, se 'aferraría' al casco mientras se hundía, llevándolo a las áreas más vulnerables de el fondo del barco.

PRUEBAS TEMPRANAS

Las primeras pruebas prácticas de una bomba lanzada desde el aire se llevaron a cabo en Fleet, la laguna protegida dentro de Chesil Beach con las bombas, que tenían hoyuelos como una pelota de golf, y pronto demostraron lo bien que podían funcionar. Ahora que se vio que la idea funcionaba, hubo un cambio de política importante que hizo que el enfoque volviera a centrarse firmemente en las represas.

33 años después de estar en la playa de Reculver para ver las caídas de prueba, Barnes Wallis regresó al mismo lugar en la costa norte de Kent.

Imagen: Ray Hepner/Charles Foster

Sería una bomba más grande, y gran parte de las pruebas ahora se están trasladando a la costa norte de Kent en Reculver, a unas pocas millas al oeste de Margate, que tenía la ventaja de que el agua era poco profunda y el lecho marino arenoso, por lo que si las carcasas de las bombas se rompían. en el momento del impacto, como sucedía a menudo, con poca agua, un grupo de trabajo podía salir y recoger los pedazos.

Ahora que el tiempo es esencial, las bombas evolucionaron hasta convertirse en un simple cilindro grande conocido como 'Mantenimiento', y la prueba final de una bomba real se llevó a cabo más lejos de la costa, en el estuario del Támesis, con resultados espectaculares. Aun así, como espectáculo, esto palidece frente a la asombrosa vista de las presas de hormigón aparentemente inexpugnables que las bombas finalmente abrirían, con resultados devastadores para el campo río abajo.

Con las técnicas de la bomba que rebota ahora como un éxito comprobado, el ritmo de desarrollo del arma antibuque se aceleró con la formación de un segundo escuadrón utilizando aviones Mosquito, y esto fue pensado como una plataforma antibuque. El desarrollo de las técnicas de ataque se trasladaría a Escocia y las aguas de Loch Striven, justo al norte del estuario de Clyde al oeste de Glasgow.

Un acorazado francés de la Primera Guerra Mundial estaba amarrado en el mar Loch, pero se pensó que esto sería seguro ya que para cuando las bombas inertes lo alcanzaran, la mayor parte de su velocidad se habría perdido. Todo iba bien hasta el día en que una bomba dio un gran rebote extra y golpeó el casco de lleno, perforando un agujero directamente en la parte superior.

Sin embargo, incluso con el gran impulso para poner las cosas en marcha, en el momento en que el arma y las técnicas de entrega estaban listas para funcionar, el Tirpitz se había hundido y la guerra en sí había avanzado, y la redada de represas terminó siendo el único uso completo. de una bomba que rebota.

HACIA ADELANTE

La idea de Barne Wallis también generó una serie de otras iniciativas, como una versión más pequeña de potencia de cohete que podría reemplazar los tubos de torpedos en un barco de torpedos a motor. El desarrollo inicial de esto tuvo lugar en el Canal de Bristol, primero en el HMS Birnbeck (el muelle que unía la isla en Weston Super Mare que apareció recientemente en All at Sea) y luego en el fuerte en el cercano Brean Down. Sin embargo, al final, esta sería otra de esas ideas brillantemente innovadoras que finalmente no llegaron a ninguna parte, tal fue el ritmo de desarrollo durante los años de guerra.

Con el regreso a la paz hubo un último hurra para las bombas rebotadoras 'Mantenimiento' que no se habían utilizado en el ataque a las presas. Los bombarderos Lancaster modificados restantes se sacaron del almacenamiento, se cargaron con las bombas (afortunadamente no fusionadas) y luego se volaron sobre las aguas hacia el noroeste de Irlanda, donde se arrojaron sin contemplaciones desde la altura al Atlántico. Algunos se habrían roto con el impacto, pero una cosa es segura: no rebotaron.

El marinero de botes con base en Solent, David Henshall, es un conocido escritor y orador sobre temas que cubren la rica herencia de todos los aspectos de la navegación de recreo.

El marinero de botes con base en Solent, David Henshall, es un conocido escritor y orador sobre temas que cubren la rica herencia de todos los aspectos de la navegación de recreo.

El post The Bouncing Bomb apareció primero en All At Sea .